It’s quite simple: We flew to Nice to get to Provence. After a lifetime of waiting, we were more than eager to sample this famous region’s food, climate, history, culture, landscape, and (in case I forgot to mention it) food.

Driving down the Côte d’Azur to Sainte-Maxime was just a necessary diversion (one of Claire’s basic principles in life is that if you are near water or horses, you must stop and enjoy them). So, after eating a proper French breakfast of croissants and baguettes, it was time to head towards the heart of Provence.

Based on prior research, we had chosen three “appetizer” destinations on today’s menu,

to whet our appetite for tomorrow’s main course: Tourves

(with its ruined castle and small roman bridge), Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume

(don’t be confused by the similar-sounding name, this town with a lovely medieval section and

basilica is different than the seaside village we visited yesterday), and Aix-en-Provence (eek! a big city!).

Based on prior research, we had chosen three “appetizer” destinations on today’s menu,

to whet our appetite for tomorrow’s main course: Tourves

(with its ruined castle and small roman bridge), Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume

(don’t be confused by the similar-sounding name, this town with a lovely medieval section and

basilica is different than the seaside village we visited yesterday), and Aix-en-Provence (eek! a big city!).

Tourves

Like other modern countries, France has a countrywide network of motorways: double-lane divided highways where you can speed along at 130km per hour without having to stop for traffic lights and circles. Zipping along the A8 péage was how we got from Le Muy to Tourves. Imagine our shock at suddenly being sent several hundred years back in time, as we downshifted from cruising a modern motorway to inching our way through the ancient, winding roads of Tourves, which seem barely wide enough to fit a single car.

To make it worse, we arrived in Tourves just when pre-school was getting out.

We had a near-crash course in how to get out of the way of opposing traffic

(by driving up on to the tiny curb of a “sidewalk” in between abandoned parked cars)

as a steady line of parents with picked-up kids headed towards us to get out of town.

Choosing when to risk leaving the curb and motor forward becomes particularly tricky

where the road curves around a building, obscuring whether someone’s headed our way.

Fortunately, we never got pinned headlight-to-headlight with another car,

much less with neither of us able to back up because of cars lined up behind us. What a mess that would have been!

To make it worse, we arrived in Tourves just when pre-school was getting out.

We had a near-crash course in how to get out of the way of opposing traffic

(by driving up on to the tiny curb of a “sidewalk” in between abandoned parked cars)

as a steady line of parents with picked-up kids headed towards us to get out of town.

Choosing when to risk leaving the curb and motor forward becomes particularly tricky

where the road curves around a building, obscuring whether someone’s headed our way.

Fortunately, we never got pinned headlight-to-headlight with another car,

much less with neither of us able to back up because of cars lined up behind us. What a mess that would have been!

The views were definitely worth the demolition derby course, however. We parked our car near a small church named after St. Francis. A ruddy-faced, ebullient man, whose more handsome son had hailed us out of his window – or so he said!, had an animated chat with Claire before directing us to the path which led to the collapsed Valbelle castle at the top of the hill overlooking the town. To get to the path, we passed by an old carved fountain (non-potable water) and up the stairs past dwelling places whose terraces were beautifully decorated with colorful flowers.

The path to the castle is quite lovely, full of forest greenery and remnants of weathered-stone ruins.

The steep angle of the narrow walkway and the superior vantage of the masonry would have given a

noticeable advantage to castle defenders. At the summit, we saw that not much was left of the medieval castle;

just a few walls and a round tower remained, surrounding a small courtyard. We explored a cool storage area underground,

located near another room that appeared to once have a kitchen hearth.

The path to the castle is quite lovely, full of forest greenery and remnants of weathered-stone ruins.

The steep angle of the narrow walkway and the superior vantage of the masonry would have given a

noticeable advantage to castle defenders. At the summit, we saw that not much was left of the medieval castle;

just a few walls and a round tower remained, surrounding a small courtyard. We explored a cool storage area underground,

located near another room that appeared to once have a kitchen hearth.

The oddest part about the castle was when we walked to the other side of a mostly intact wall

to discover a very different style of architecture: the wall had been decorated by a line of

neo-classical pillars in front of a spacious two-level garden lawn and obelisk.

From this lawn overlooking the town, we spotted a prominent statue on a narrow hill (perhaps a Virgin Mary on the Rocks?).

This area, with its odd colonnade wall, seemed like it could be a decorative backdrop for some sort of

night-time theatre or concert.

From this lawn overlooking the town, we spotted a prominent statue on a narrow hill (perhaps a Virgin Mary on the Rocks?).

This area, with its odd colonnade wall, seemed like it could be a decorative backdrop for some sort of

night-time theatre or concert.

Later research confirmed our suspicions. In the 1770s, the decadent Comte extravagantly rebuilt and decorated the medieval castle and gardens to create a Provincial Versaille worthy of visits by Voltaire and others. It was seized during the French Revolution and eventually destroyed in 1799 by a fire in the castle’s garrison. What statuary and stone was left was carted off by the villagers. Various sites around town still feature carvings from the briefly magnificent castle.

![]()

Tourves considerably pre-dates its Valbelle feudal origins in 1170.

A millennia before then, it was a minor way station along the Via Aurelia (the main motorway of its time)

which connected Marseilles and Aix to Imperial Rome. We decided to visit the ruins that remain.

After nearly getting stuck on the wrong dirt road (where turning around risked plummeting down a steep hill),

we steadied our nerves with a baguette and a block of soft cheese.

Somehow, we reversed course and navigated our way through signless country roads to the well-preserved

Roman bridge found deep in a forest park a few kilometers south of the modern town.

Somehow, we reversed course and navigated our way through signless country roads to the well-preserved

Roman bridge found deep in a forest park a few kilometers south of the modern town.

A decent size stream runs through a somewhat narrow valley. One side features a prominent, vertical rock face. A rocky incline goes steadily up the other side. Walking a dirt path past an olive grove and farmlands, we entered the woods and eventually located the sturdy, arched bridge built over the stream.

Even today, this Roman pont looks strong and level enough to support Roman chariots needing to quickly cross the stream

or even transport large, quarried stone. Further through the woods, we found what might have been a

domed stone pipe that led down the rocky hill from other ruins, a dam, and a square aqueduct that split off from the stream.

It was fascinating to see how much remains after 2,000 years of wear and tear,

now overgrown by a woodland forest that gurgles away in quiet serenity.

Only one other small family visited at the same time.

They left quickly, leaving us in peace to enjoy the place in our own way.

Even today, this Roman pont looks strong and level enough to support Roman chariots needing to quickly cross the stream

or even transport large, quarried stone. Further through the woods, we found what might have been a

domed stone pipe that led down the rocky hill from other ruins, a dam, and a square aqueduct that split off from the stream.

It was fascinating to see how much remains after 2,000 years of wear and tear,

now overgrown by a woodland forest that gurgles away in quiet serenity.

Only one other small family visited at the same time.

They left quickly, leaving us in peace to enjoy the place in our own way.

As a side note, if Roman ruins are still not ancient enough, feel free to visit the prehistoric cave (which we did not see), located not far from the Roman ruins. They features a number of painted symbols from so far before recorded history that we may never fully understand them. Like many towns in the Mediterranean, Tourves evidently has very deep historical roots.

Before we left town, we found a nice restaurant on the main street. We sat in the large courtyard out back, surrounded by medieval walls that have seen many patches over the centuries. Claire was able to check a delightful foie gras off her must-eat list. Jonathan enjoyed a tasty prawn dish.

Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume

Few ruins remain to show that St. Maximin was the next agricultural outpost along the Via Aurelius.

Perhaps the roman stonework was re-purposed when the town grew rapidly after the

discovery in 1279 of the tomb of Mary Magdalene. Church lore claims that Mary had fled from Jerusalem

to Marseille (in a crippled boat, no less) with her brother Lazarus and St. Maximin, a 4th century bishop.

She converted the locals, retired to caves near town, was buried in style after death,

and then was forgotten until the discovery of her tomb.

Few ruins remain to show that St. Maximin was the next agricultural outpost along the Via Aurelius.

Perhaps the roman stonework was re-purposed when the town grew rapidly after the

discovery in 1279 of the tomb of Mary Magdalene. Church lore claims that Mary had fled from Jerusalem

to Marseille (in a crippled boat, no less) with her brother Lazarus and St. Maximin, a 4th century bishop.

She converted the locals, retired to caves near town, was buried in style after death,

and then was forgotten until the discovery of her tomb.

With the enthusiastic encouragement of cultists and the blessing of the pope,

the King of Naples (who was also the count of Provence) launched construction of a massive basilica to properly house Mary’s remains.

Work continued over the next 250 years, interrupted by the Black Plague, drawing

untold numbers of fervent pilgrims.

Now, here we were, the most recent pilgrims, paying our respects to this church and the old town that supported it.

Work continued over the next 250 years, interrupted by the Black Plague, drawing

untold numbers of fervent pilgrims.

Now, here we were, the most recent pilgrims, paying our respects to this church and the old town that supported it.

Our first sight of the basilica was of a side wall covered in scaffolding. Despite construction having been halted nearly 500 years ago, leaving the building somewhat unfinished, reconstruction work was in full bloom. We walked past the attached visitor center and luxury hotel, through the noise and dust of the elevated stone masons using power tools, to arrive at the public courtyard that gives a magnificent view of the church’s imposing front wall.

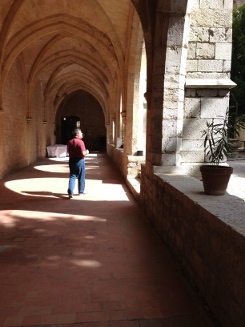

There is an enclosed courtyard beside the basilica, decorated with the shadows of roofed walkways and the flying buttresses

of the gothic church to one side. It is a lovely place to sit and walk, with hedges and trees, places to

sit, ancient stone carvings, and amazing views of the multi-layered architecture.

There is an enclosed courtyard beside the basilica, decorated with the shadows of roofed walkways and the flying buttresses

of the gothic church to one side. It is a lovely place to sit and walk, with hedges and trees, places to

sit, ancient stone carvings, and amazing views of the multi-layered architecture.

Within the church, the nave is lavishly appointed, filled with paintings, gold trimmings, and wood carvings (including an upraised massive chair installed against one column). A walled-off choir lies beyond the public altar. On the other side, above the entrance, are the organ’s gold pipes.

From one side aisle, we descended down past strange horseshoe symbols carved in the stone wall

to the small underground crypt which dates considerably earlier than the basilica.

This is where we found the reliquary skull of Mary Magdalene and four sarcophagi. One can only imagine how many people

have crowded into this dark, dank space in hopes of getting blessed somehow by what remains of this holy companion of Jesus.

From one side aisle, we descended down past strange horseshoe symbols carved in the stone wall

to the small underground crypt which dates considerably earlier than the basilica.

This is where we found the reliquary skull of Mary Magdalene and four sarcophagi. One can only imagine how many people

have crowded into this dark, dank space in hopes of getting blessed somehow by what remains of this holy companion of Jesus.

Outside the church, the narrow, winding streets of the old town are crowded with people shopping at the modern gift shops and clothes stores that now occupy and redecorate ancient multi-story stone buildings. Remnants of older culture can be found, such as the public washing area where residents can still bring their dirty clothes. In solidarity with pilgrims parched from their dusty travels in the hot sun, we sat under the shade at an outdoor cafe and sipped on cold Orangina.

Aix-en-Provence

Like many European cities, Aix is inordinately proud of her most famous painter, Paul Cézanne.

They have several museums and historical sites dedicated to him, along with flapping banners

on many city posts that advertise his presence and genius.

Our favorite reminder of Cézanne came when we saw the

magnificent limestone mountain range (Montagne Sainte-Victoire) that Cezanne featured in many of his

paintings. It followed us on the right hand side of the motorway towards Aix, raised up from the farmland plains,

just as it surely would have followed Roman travellers along the Via Aurelius.

Our favorite reminder of Cézanne came when we saw the

magnificent limestone mountain range (Montagne Sainte-Victoire) that Cezanne featured in many of his

paintings. It followed us on the right hand side of the motorway towards Aix, raised up from the farmland plains,

just as it surely would have followed Roman travellers along the Via Aurelius.

It was on this motorway, as we sorted out where to stay for the night, that we discovered that our rental car had a fabulous built-in GPS, far more free than the expensive GPS we declined when offered by Avis. After careful calculation, the GPS plotted a route through the center of Aix as the fastest way to get to our chosen hotel. Oops!

Aix is a good size city. Before long, we were negotiating our right of way against end-of-day

commuters through narrow, one-way alleys, narrowly missing tourists infesting the boulevards,

and circling the 5-way traffic circle at Place du General de Gaulle to turn around.

The low point of our reluctant trip through the city came when we followed a bus into an

ancient section of town that protected itself from most traffic with obstruction pillars that

sank into the ground to allow passage when presented with the right card. We did not notice the bus

had done that for us until a few minutes later when we found our exit from the district blocked by another such pillar.

Aix is a good size city. Before long, we were negotiating our right of way against end-of-day

commuters through narrow, one-way alleys, narrowly missing tourists infesting the boulevards,

and circling the 5-way traffic circle at Place du General de Gaulle to turn around.

The low point of our reluctant trip through the city came when we followed a bus into an

ancient section of town that protected itself from most traffic with obstruction pillars that

sank into the ground to allow passage when presented with the right card. We did not notice the bus

had done that for us until a few minutes later when we found our exit from the district blocked by another such pillar.

Fortunately, we found a call button next to the card reader. After pleading our ignorance in fractured, accented French, someone pushed the magic button (sighing no doubt at “les touristes”) which lowered the pillar and set us free. This is the nearly the only time the GPS got us into trouble; it became an invaluable travel assistant.

We settled in our 19th century hotel (Le Prieuré) just outside the city, whose rooms overlooked a wonderfully

landscaped garden (complete with extensive No Trespassing signs). We headed back into the city for dinner

(walking instead of driving the inner city). The meal of trotters and bouillabaise was ok,

but not as attentive to flavors as we had found in more rural eateries.

We settled in our 19th century hotel (Le Prieuré) just outside the city, whose rooms overlooked a wonderfully

landscaped garden (complete with extensive No Trespassing signs). We headed back into the city for dinner

(walking instead of driving the inner city). The meal of trotters and bouillabaise was ok,

but not as attentive to flavors as we had found in more rural eateries.

Aix has a reputation for charming its visitors, as described lovingly by Guy Gabriel Kay in his fantasy novel Ysabel, magically weaving together modern scenes and characters with Roman and Celtic ghosts and rites. Disappointingly, our experience was of a too-large and over-busy city. We decided not to linger any further in Aix. Instead, we would get a good night’s sleep and then head out to explore the medieval villages of Luberon.